In our concrete bumper sticker world, or the Twittersphere, all sorts of words (old and new) and quotations (old and new) come our way like so many points of sunlight, although they reach us a lot faster than eight minutes and twenty seconds. Anonymous or pseudonymous bloggers and Know-Nothing celebrities and politicians can claim a Voltaire or Churchill quotation or Ronald Reagan quip as one of their own, even if, it turns out, that Churchill or Voltaire or Reagan never really said it in the first place, or might have been quoting someone else themselves. We’ve come a long way, still, from “The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls and tenement halls.” We’ve come an even longer way from a time when people (and students) actually held physical books in their hands and underscored a memorable passage or line that they thought was important and worth remembering. And we can barely recall when people would take the time to write down something they just read.

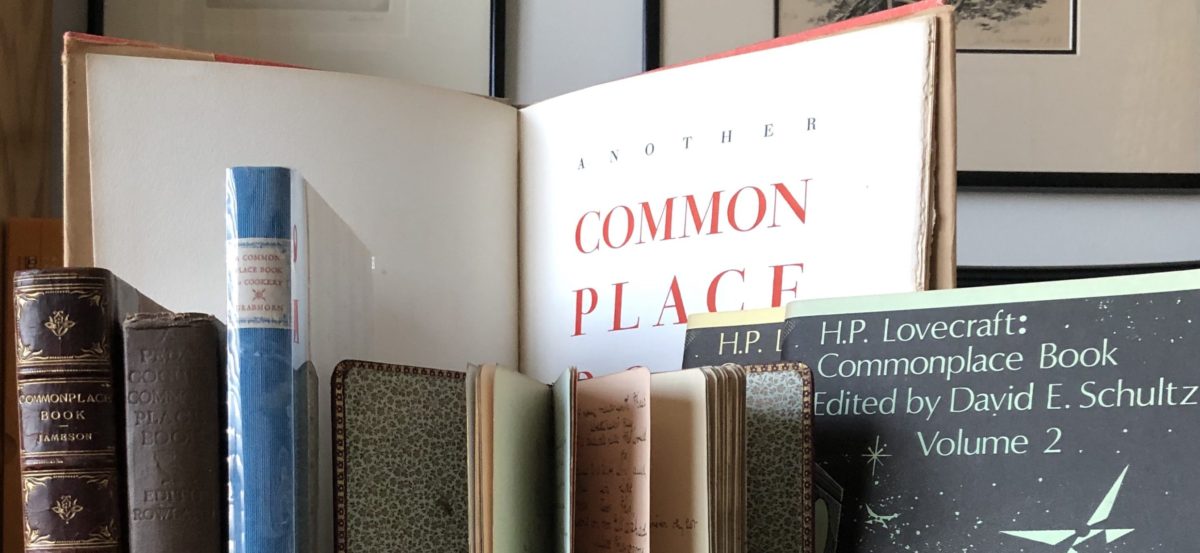

When people did start writing things down years ago–in journals, diaries, notebooks, and scrapbooks–many kept special books just for quotations. These books came to be called commonplace books, after the notion that there were certain arguments, ideas, and topics (such as “wisdom” or “justice” or “beauty”), hence the “common places,” which could be categorized or labeled and later broken down further into subtopics and subheadings, in which sagacious or even practical comments or observations and strongly held beliefs, coming down from—at least at first—antiquity and scripture, might be held in common and learned and passed down, perhaps even memorized. By common, those early anthologizers meant something like a common heritage or common knowledge or common belief worth preserving, including the geographical spaces where these ideas first came from (Athens>Jerusalem>Rome, a.k.a. Western civilization, for the most part) as well as the physical places (the oral and written sources) the quotations came from (the Bible and the pagan writers of antiquity through medieval times–Hippocrates, Plato, Aristotle, St. Paul, Sun Tzu, Laozi, Augustine, Mohammad, Maimonides, Confucius, Aquinas, and so on down the list of the Great books and thinkers). In the end, geography hardly mattered. Western civilization was more of an idea than a place, which could be transmitted at all times and for all peoples and to all places, just as the ideas coming from non-Western civilizations could enter its own canon of great books and wisdom through translations and university curricula and commonplace books. Western culture, which began in such narrow confines, became an argument with itself, despite those who would jettison those original common places for whatever –ism-of-the-week happens to bother them (“Hey, ho, Western culture has to go!”).

Originally commonplace books were meant to be a device for effecting memory of these significant ideas, which, barring a razor-sharp retention, if not written down (especially in a time in before the printing press to the time in which book ownership was still a privileged thing) might be forgotten if not lost forever.

While the concept of the common places preceded commonplace books, annotations and shared annotation go back at least as early as the 2nd century CE. The Talmud, which is something of a gloss of a gloss of a gloss, seems as good a starting place as any. In the standardized, written Talmud, which was oral to begin with, we can actually see and read those marginal annotations, as they became part of the second most important book in Judaism and foundation of modern Judaism. Owen Gingrich, in The Book Nobody Read: Chasing the Revolutions of Nicholaus Copernicus, writes of his tracking down the surviving first copies of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus and discovering many with multiple readers’ markings and marginal notes, which moved from owner-to-owner. Annotation would become a useful and crucial tool in commentary and argumentation, but it was clear that the point of that commentary or argument was often something specific that the original author had said or written, which the annotator was copying and responding to or taking issue with, even, at times, correcting errors

Commonplace books seemed to follow the trajectory of reading and subject matter over the centuries. They evolved from more or less specialized types of books (in theology, science, and law) often to very personal ones, wider in scope, subject matter, and choice of authors. I like to think of the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius as an early example of the latter, although any sort of “book” wasn’t Marcus’ intention in his posthumously published work, written solely for his own edification–but that’s also what makes it so much a commonplace book. The idea behind it was to record not only his own personal observations and learning but also the wisdom or sententiae of his family members, teachers, and the Greek and Roman, mostly Stoic, philosophers, who influenced him most. The intention of Medieval commonplace books, in the form of florilegia, both theological and otherwise, and those of the Renaissance, was largely pedagogical: how to live a moral life, just as the pagan Marcus strived to know how to live a “good” (i.e. virtuous) life.

Through the Enlightenment and Victorian eras, and well into the 20th century, commonplace books became filled with quotations coming from contemporary topics and subheads and more varied sources, such as newspapers, sermons, lectures, literature (predominantly poetry), and intimate conversations. Some commonplace books were simply filled with the words of others, famous and not famous, and some contained original thoughts and material as well.

By the late 20th century, commonplace books had all but disappeared. In an age in which information can be accessed within seconds and cut and pasted into a Word document, no one bothers to remember much of what they read, nor do they bother (as often as they should) to check the accuracy of what they are reading and copying. Not only does that not aid memory (it may even hinder it), but it also explains the paucity of greater understanding and critical thinking. The same technology, ironically perhaps, or not so ironically, has made it possible to revive interest in commonplace books by way of instant access, to sites such as this one and the links I provide to others who share this same interest, as well as to things like BrainyQuotes; a plethora of “quote-a-days” on almost any topic or famous person; and endeavors like Bartleby.com, which offers links to Bartlett, Grocott, Hoyt, Hazlett, Christy, etc., all of which might encourage people to read the actual sources where the quotes came from and become “commonplacers” themselves.

+++