William Byrd II (1674-1744) was an important figure in the history of colonial Virginia: a founder of Richmond, an active participant in Virginia politics, and the proprietor of one of the colony’s greatest plantations. But Byrd is best known today for his diaries. Considered essential documents of private life in colonial America, they offer readers an unparalleled glimpse into the world of a Virginia gentleman. This book joins Byrd’s Diary, Secret Diary, and other writings in securing his reputation as one of the most interesting men in colonial America.

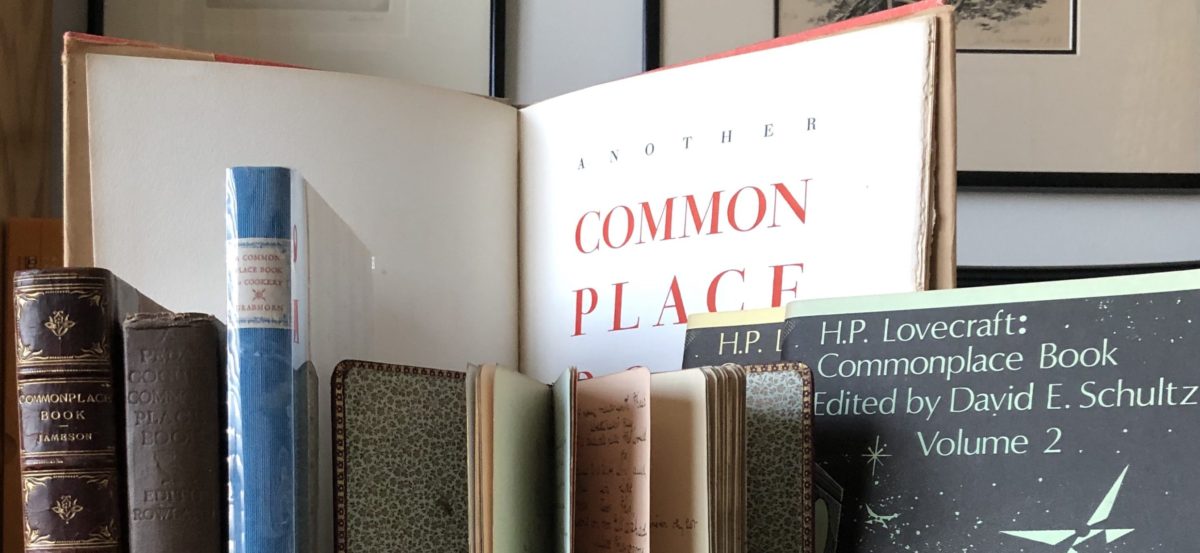

Edited and presented here for the first time, Byrd’s commonplace book is a collection of moral wit and wisdom gleaned from reading and conversation. The nearly six hundred entries range in tone from hope to despair, trust to dissimulation, and reflect on issues as varied as science, religion, women, Alexander the Great, and the perils of love. A ten-part introduction presents an overview of Byrd’s life and addresses such topics as his education and habits of reading and his endeavors to understand himself sexually, temperamentally, and religiously, as well as the history and cultural function of commonplacing. Extensive annotations discuss the sources, background, and significance of the entries.

“Many entries must have come from conversation and table talk, and as such they defy any attempt to discover sources. Few of the manuscript’s humorous anecdotes, jokes, scandalous tales, and gossip seem to appear in print before the common book period.” The editors thus provoke the longstanding dilemma regarding the provenance of certain commonplace quotations while asserting that “opportunities to extend the research we have initiated here abound. We welcome future developments.”

“That love that enters at the ears takes faster hold of our heart than that which enters in at the eyes.”–from The Commonplace Book of William Byrd II of Westover

Milcha Martha Moore (1740-1829), who lived in the Philadelphia-area during the American Revolutionary War period, was famous for the anthology The Miscellanies, Moral and Constructive (1787), which was used in American public schools and went through several editions. Her commonplace book, unpublished until 1997 by Penn State University Press, was a compilation of poetry and prose, which in manuscript form had been widely circulated among her close circle of friends. “Moore was documenting,” writes Karin A. Wulf in her introduction, “her affiliations as much as she was conserving a body of work and copying their significant writings. These works knitted Milcha Moore and her circle closer together.”

Moore’s commonplace book comprised over100 selections, crossing various genres (meditations, letters, journal writing), of three notable women writers of the period: Susanna Wright, Hannah Griffitts, and Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, many published here for the first time. Other notable entries include Ben Franklin’s epitaph he wrote for himself and several other entries by him; Patrick Henry’s letter to the abolitionist Robert Pleasants; an unattributed letter sent to the Quaker minister Samuel Fothergill; and poems by the loyalist Jonathan Odell.

The publisher writes, “While scholars have speculated about the extent to which elite women exchanged ideas through reading and writing during this period, Moore’s Book is the richest surviving body of evidence revealing the nature and substance of women’s intellectual community in British America.”

The commonplace book portends how the rise of printed material began to change the direction of American letters, which was heretofore a manuscript culture. Understood in the context of the American Revolution and Quaker culture, Milcha Moore’s Book provides a glimpse into a literary life, which “be[lies] the notion that women’s concerns were limited only to a domestic sphere.”

Since the Men from a Party, on fear of a Frown,

Are kept by a Sugar-Plumb, quietly down,

Supinely asleep, and depriv’d of their Sight

Are strip’d of their Freedom, and rob’d of their Right.

If the Sons (so degenerate) the Blessings despise,

Let the Daughters of Liberty, nobly arise,

And tho’ we’ve no Voice, but a negative here,

The use of the Taxables, let us forbear,

(Then Merchants import till yr. Stores are all full

May the Buyers be few and yr. Traffick be dull.)

Stand firmly resolved and bid Grenville to see

That rather than Freedom, we’ll part with our Tea

And well as we love the dear Draught when dry,

As American Patriots,—our Taste we deny, —from “The female Patriots” Address’d to the Daughters of Liberty in America, 1768 (Hannah Griffitts) in Milcha Martha Moore’s Book